Sculpture

“I started out as a sculptor in which I explored ideas about space. And space is meaningless without light.”

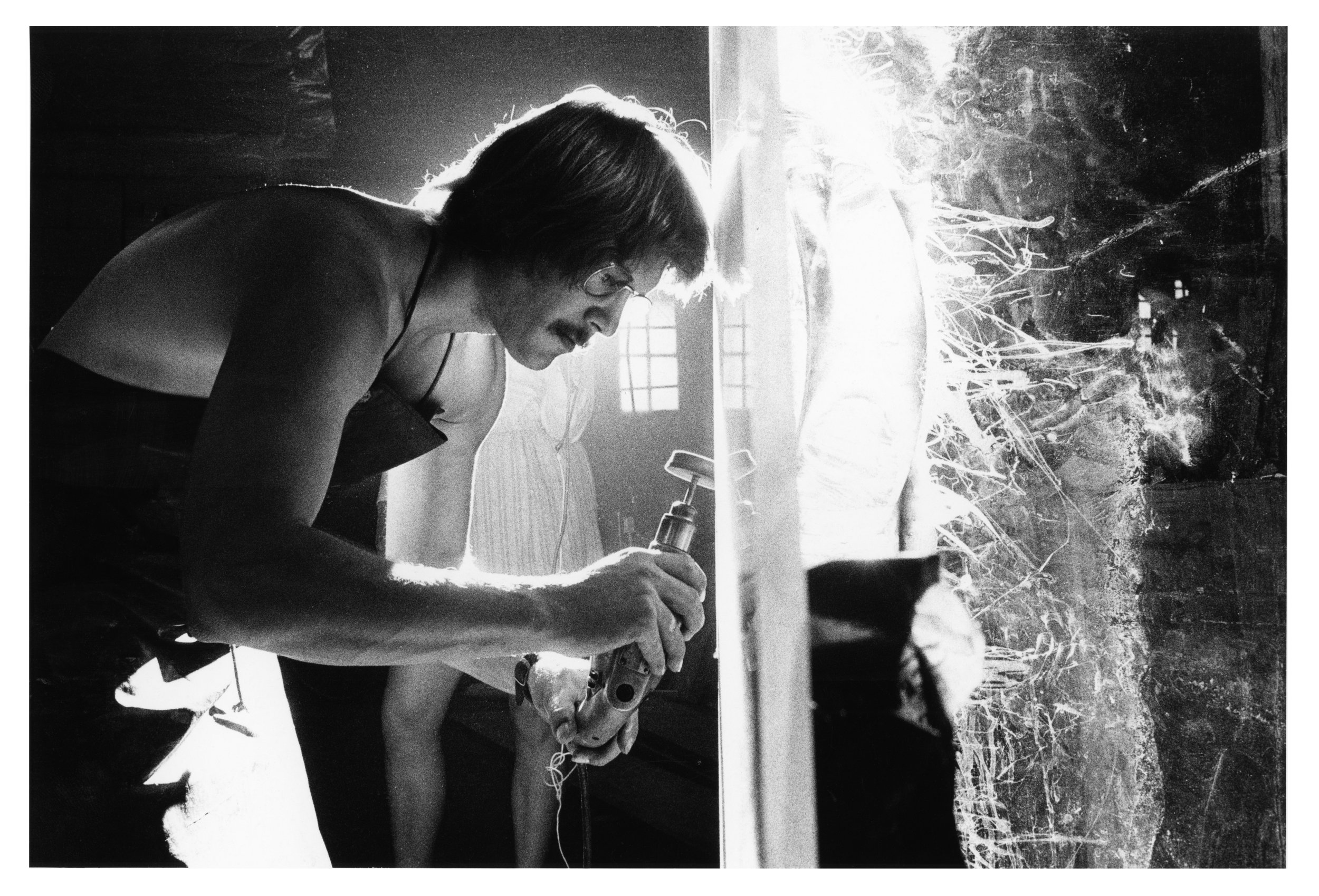

At one point, Krebs said, he constructed sculptures of transparent plexiglass. “I walked away from it, turned around, and it seemed to have disappeared. At that moment the idea was triggered to work with lasers. I liked the idea of structuring things in space that aren’t material.”

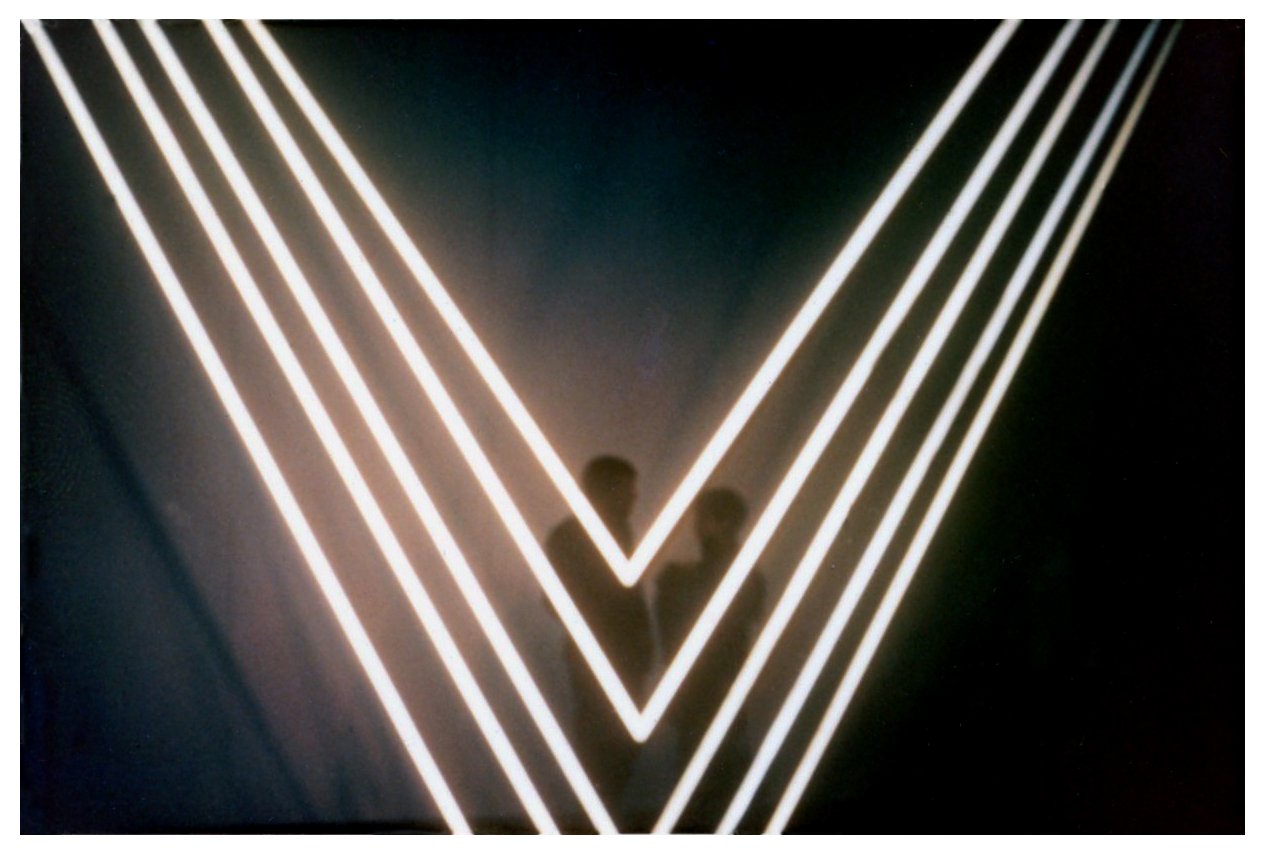

Krebs, 48, who built his first laser installation in 1968, said, “I’ve always said I wanted to build sculptures that people would walk through.”

Jack Garner, Sculpture in the Sky: Rochester will be wrapped in light in ‘Neo-Green,’ Democrat and Chronicle, Rochester, NY, 1987

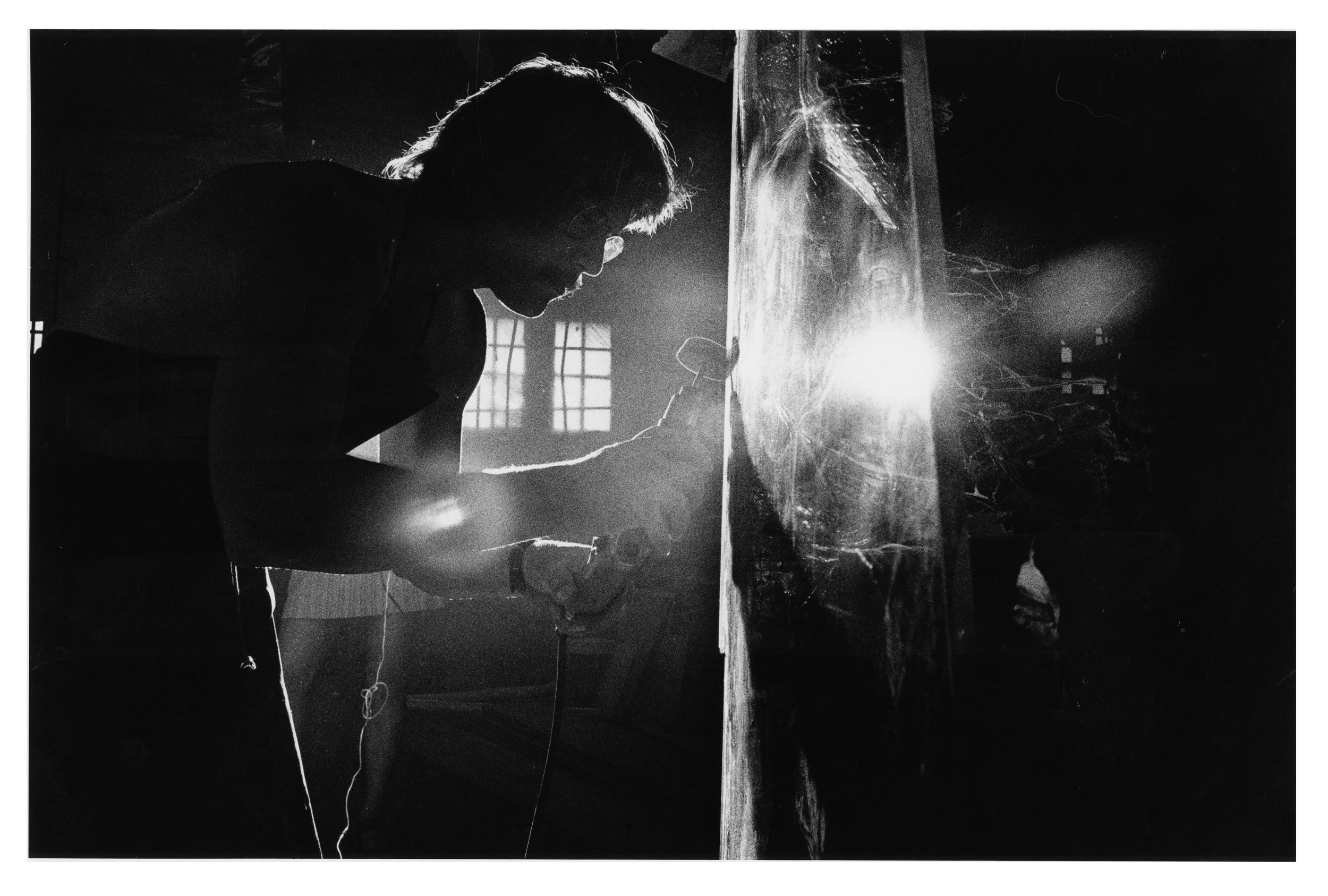

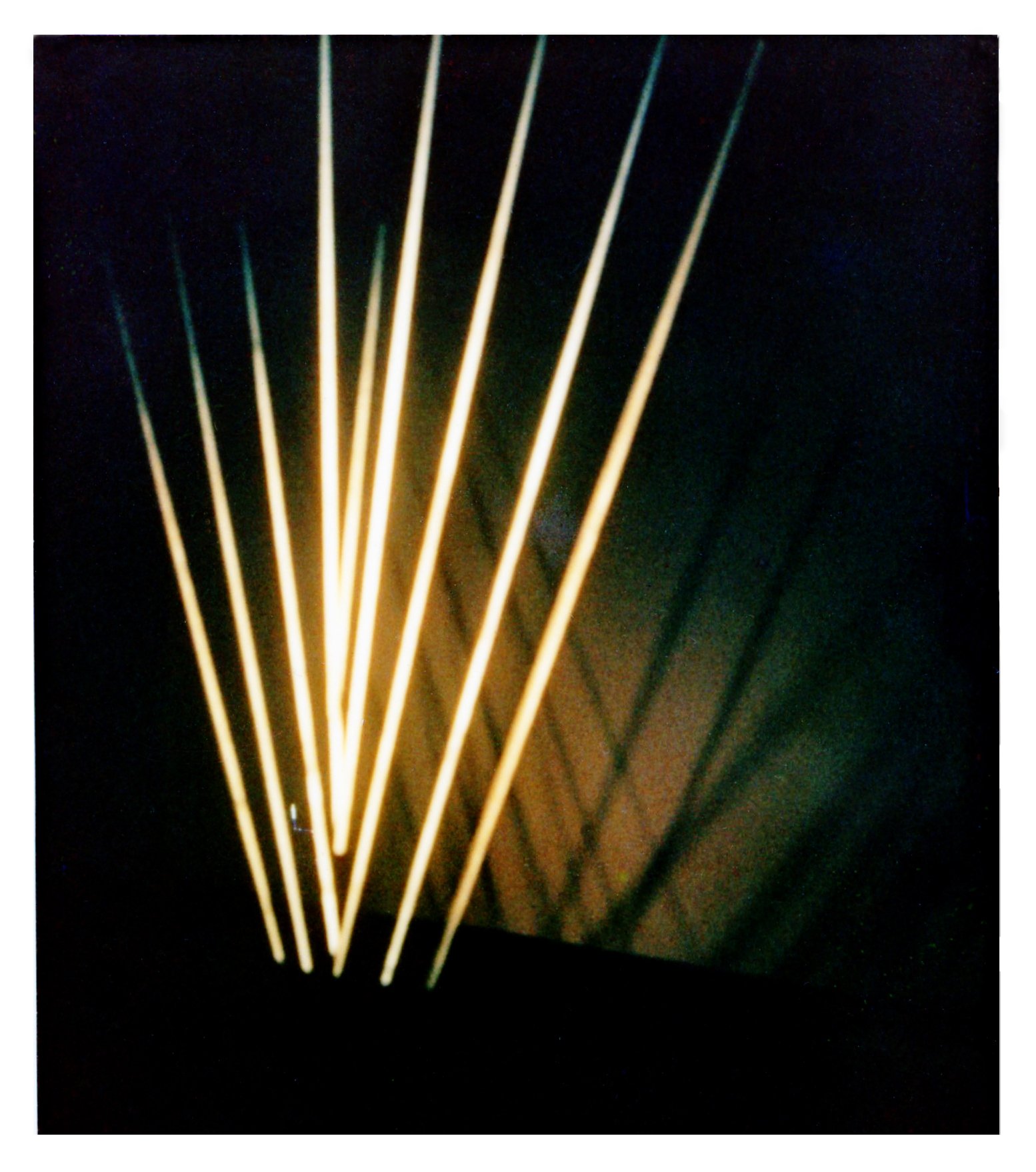

Rockne Krebs, 1968, in his Washington, DC studio.

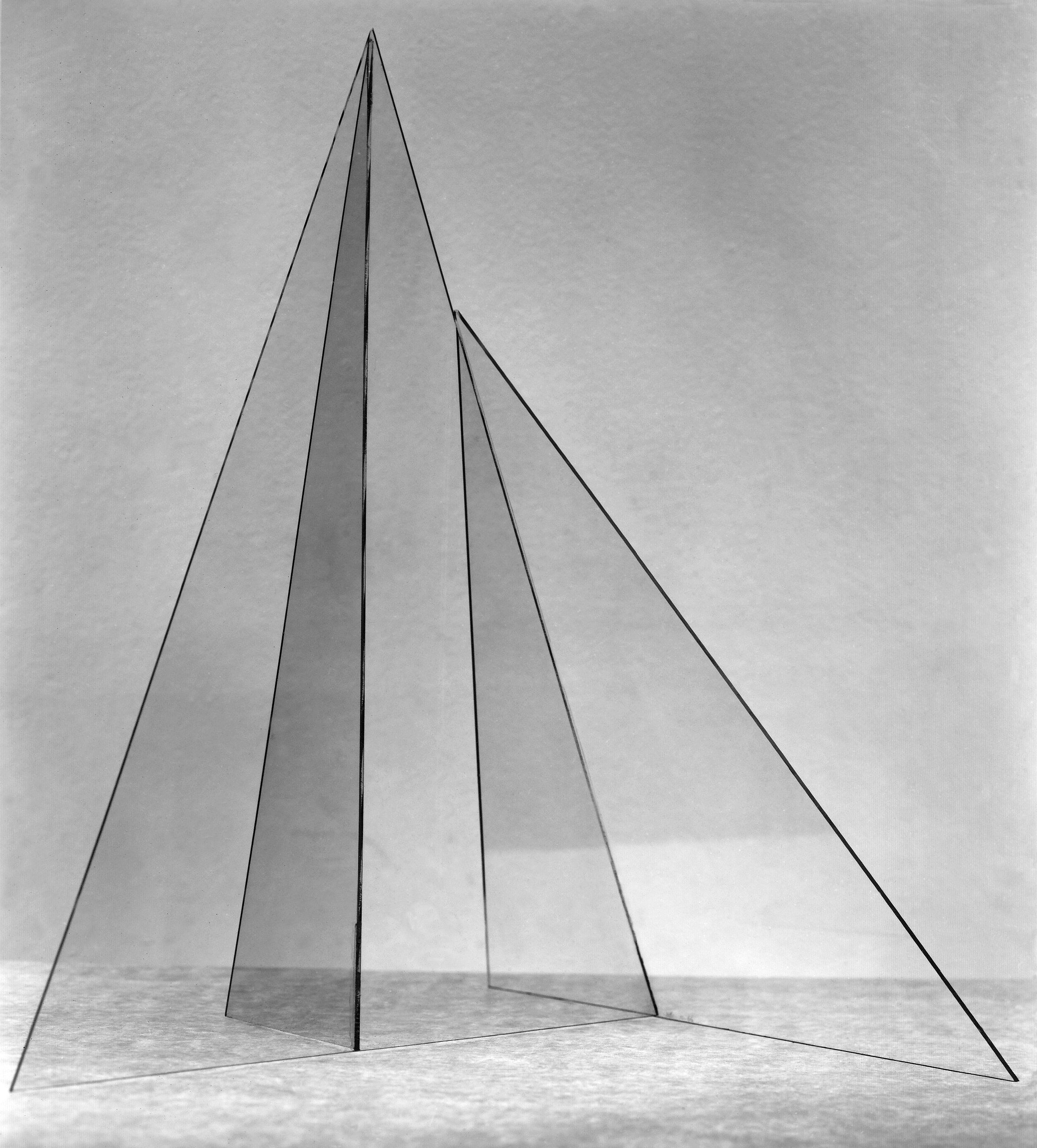

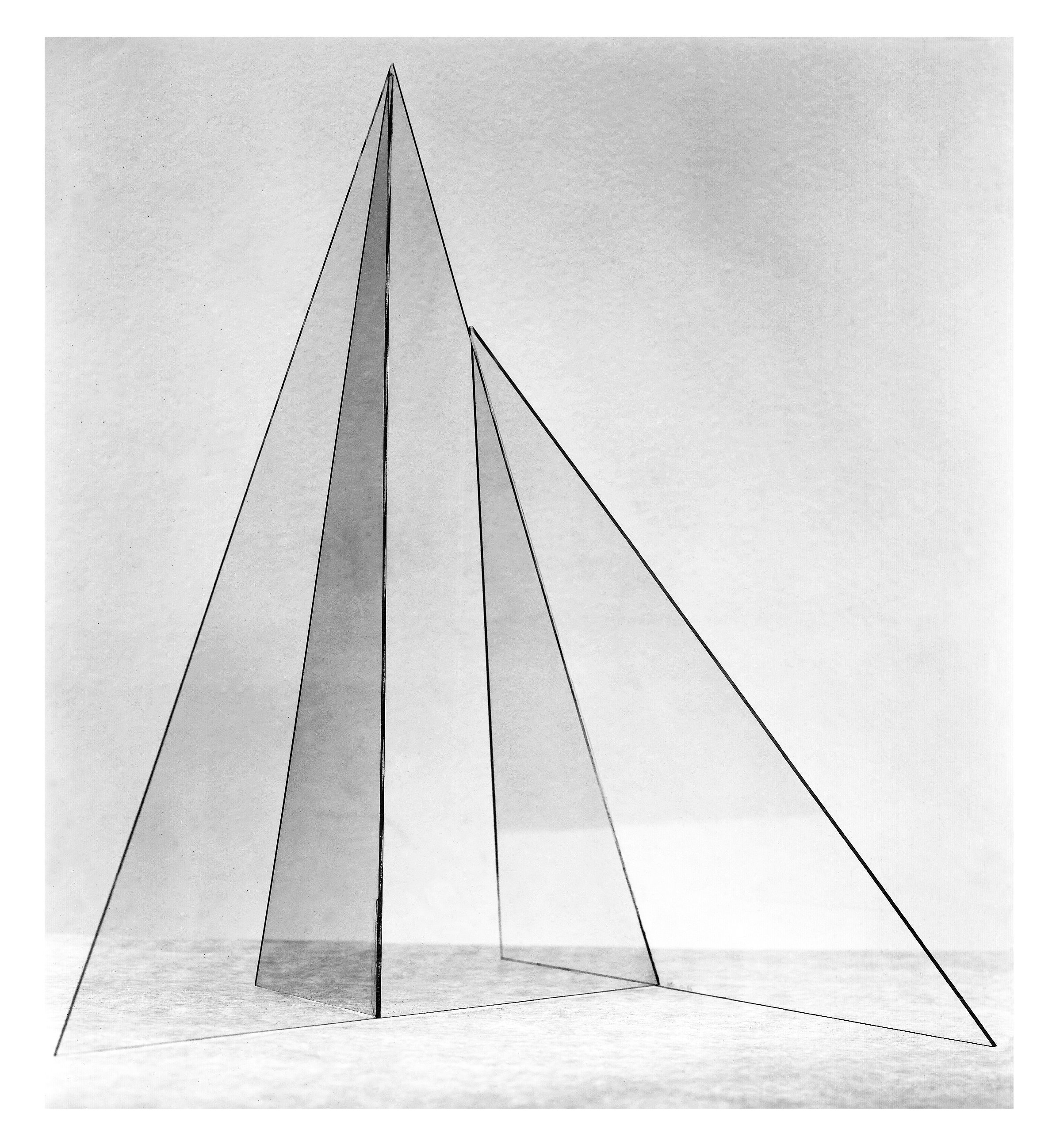

“Actual space is the medium of sculpture. A transparent object occupies space, yet it approached visual non-materiality because it can absent itself from the milieu. Paradoxically, when this occurs, perception of the space is intensified. The viewer is compelled to consciously locate and define for himself the space the sculpture occupies, even while the transparency continually confronts him with his environment. The six planes that form the interior space through which his body is moving become the armature of the sculpture.” Rockne Krebs, 1967

Leslie Judd Ahlander, Art in Washington 1969, 1968, published by Acropolis Books.

Archive Art Blog post: 2/9/2014

The Plexi Pieces - Krebs’ Glistening Geometrical Sculptures

1962-1965 United States Navy

1965 Trip to Bennington College, Bennington, Vermont to visit

Anthony Caro and Kenneth Noland.

Began plexiglass pieces.

1967 First experimentations with lasers, ideas for projection of color transparencies into a controlled atmosphere of vapor.

"Krebs responded deeply to the work of sculptor Anthony Caro and visited Caro at Bennington College in Vermont where he, as well as Kenneth Noland, was teaching. While Krebs’s exposure to art is extremely broad, the work of Noland and Caro has been the most immediately influential. The most remarkable aspect of Krebs’ s study of the work of Noland and Caro is the speed with which he was able to grasp the problems they were presenting in their art and then the speed with which he was able to apply this toward solutions all his own.

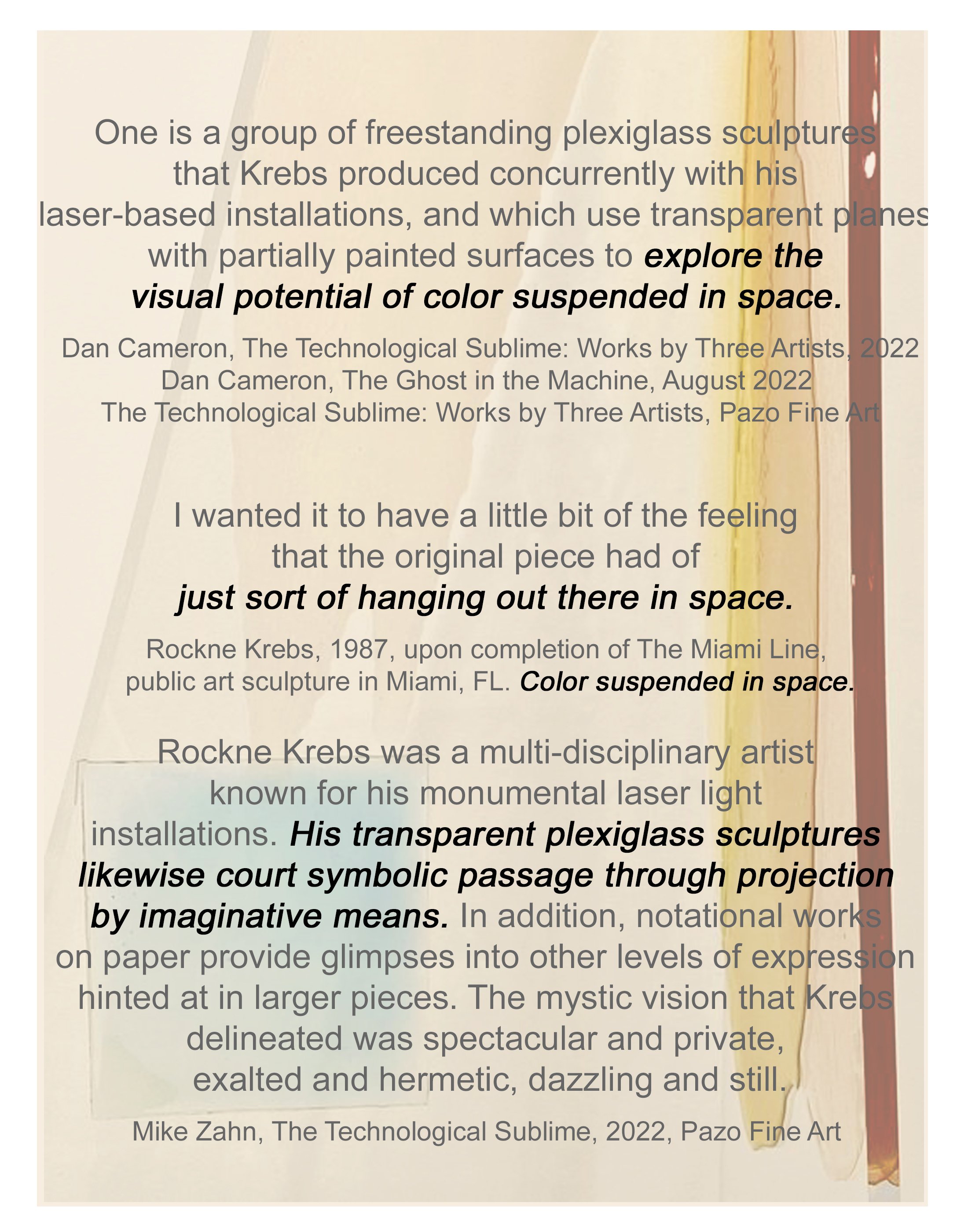

From these first triangular plexiglass works to the complex forms in clear plexiglass with pigmented resin in their seams…the reduction of the material requirements of sculpture and the resulting demands on the viewer’s perception have been continuous. While the pristine forms and handsomely crafted materials in these sculptures are an undeniable part of their appeal, their strength lies primarily in their creation of ambiguity….The ambiguity in Krebs’ plexiglass pieces centers on their opposing qualities of concreteness and transparency…. Later the edges of the plexiglass forms were beveled to create a greater end surface and pigment was added to the resin used to join the separate sections. The result...was a glowing configuration of colored light supported by transparent planes."

James N. Woods, Rockne Krebs, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, 1971

“His materials vary but his concerns remain the same. All his sculptures deal with space-space explored and occupied by glowing lines of light. Krebs’ laser lines vanish at the throwing of a switch. His plastic lines are permanent but their look is equally insubstantial, luminous and pure…They’re generated by the plexiglass he works with….The planes are colorless, but their edges glow.” Paul Richard, The Artful Showing of Space, Light and Geometry, The Washington Post, 1969.

“….an exhilarating atmosphere of pure form... his growing mastery both of theory and technique has been an impressive thing to observe…Krebs’ work in plexiglass based upon an ingenious variety of conformations of the right triangle, is stunningly beautiful, a demonstration of the poetry of pure forms.” Benjamin Forgey, ART: the Pure Form of Krebs, The Washington Star, 1969

“The sculpture seems to change as the viewer moves around it. Seen from the outside, the diagonal edges of the parallel walls overlap in the field of vision, forming a glistening X that shifts proportion as the viewer moves his head….all the while, the shadows and reflections cast by Clear (5’ wide x 12’ high) are responding precisely to the clouds and people moving around it and to the movement of the sun…displayed outdoors for HemisFair ’68, the world’s fair in San Antonio, TX. More than seven million people are expected to look at – as well as through – a Krebs sculpture of transparent Plexiglass...” Paul Richard, HemisFair Sculpture, The Washington Post, 1968

“Actual space is the medium of sculpture. I want to grasp the peculiarities of this medium and to force perception of the sculptural space to a conscious level….A transparent object occupies space, yet it can absent itself from the milieu. When this occurs, the viewer is compelled to locate it and define for himself the space it occupies. Perception of the space becomes a conscious act.The sculptures exist without an image and maintain a curious detachment from the surrounding space, even while their transparency continually confronts the viewer with his environment. The six planes that form the urban interiors through which our bodies move become their armature. “ Rockne Krebs, December 1967, Artists on Their Art, Art International, Volume XII/4, 1968

“No Land has bands of color with a clear area in the middle where one can see through the sculpture. It changes as one looks at it. Sometimes it looks as if color came out of the ground, made a sharp angled turn (like a light beam bouncing off a mirror), then went back into the floor. Other times, it looks like a mountain. Influenced by Washington Color School painters, Krebs made something solid yet transparent, and not at all dependent on canvas or even a wall to hang it on. From this he went on to work primarily with light. One can see a hint of his light works in No Land, as he begins to give color its freedom.”

Ianthe Gergel, Obituary: Rockne Krebs, 1938-2011, Experiment Station, a blog by The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, November 4, 2011

No Land, 1966. Photographed by Krebs outside of his studio, 1966.

Rockne Krebs with Pi Flower (1968), Jefferson Place Gallery, Washington, DC, 1969. A painting by Sam Gilliam is in the background. Photograph by Steve Szabo for The Washington Post. Photograph from the article The Artful Showing of Space, Light and Geometry by Paul Richard, The Washington Post, 1969. A review of Rockne Krebs: Energy Structures.

Antarctic Flower, 1969, 73 x 32 x 38” Photo © The Spencer Museum of Art, 2013 “Three triangular forms in clear plexiglass of descending size, nested within the largest form. Each object comprises two joined right-triangular panels. The glue along the center seam of each object alternates clear and transparent cobalt blue. The highly polished edges of each panel refract light, from the center, appearing to also be striated with blue in addition to the spectrum of color created by the prismatic plexiglass." The Spencer Museum of Art

(con't from previous image) and transparent cobalt blue. The highly polished edges of each panel refract light, from the center, appearing to also be striated with blue in addition to the spectrum of color created by the prismatic plexiglass." The Spencer Museum of Art. Antarctic Flower, 1969. Photo © The Spencer Museum of Art, 2013

XXI, 1967, 48 x 72 x 72” Rockne Krebs: Sculpture, 1967, Byron Gallery, New York, NY, exhibit installation photograph.

Rockne Krebs at the Byron Gallery, 1967, New York, NY

Untitled, 1968. Photographed in Krebs’ Johnson Avenue studio in the Shaw neighborhood of Washington, DC, 1969. “I started out as a sculptor in which I explored ideas about space. And space is meaningless without light.” At one point, Krebs said, he constructed sculptures of transparent plexiglass. “I walked away from it, turned around, and it seemed to have disappeared. At that moment the idea was triggered to work with lasers. I liked the idea of structuring things in space that aren’t material.” Jack Garner, Sculpture in the Sky, Democrat and Chronicle, Rochester, NY, 1987

No Land, Rockne Krebs, 1966, 66.5 x 96 x 60” Photo taken outside of Krebs’ studio in the Adams Morgan neighborhood in Washington, DC, 1966. Coll: The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, Gift of Sam Gilliam, 1980. "No Land has bands of color with a clear area in the middle where one can see through the sculpture. It changes as one looks at it. Sometimes it looks as if color came out of the ground, made a sharp angled turn (like a light beam bouncing off a mirror), then went back into the floor. Other times, it looks like a mountain. (con't next image)

No Land, Rockne Krebs, 1966, 66.5 x 96 x 60” coll: The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC. Photo: © Carol Harrison, 2024. (con't) "Influenced by Washington Color School painters, Krebs made something solid yet transparent, and not at all dependent on canvas or even a wall to hang it on. From this he went on to work primarily with light. One can see a hint of his light works in No Land, as he begins to give color its freedom.” Ianthe Gergel, Obituary: Rockne Krebs, 1938-2011, Experiment Station, a blog by The Phillips Collection, November 4, 2011

Untitled, 1966

Untitled, 1985. 97 x 32.5 x 24” Photo courtesy of Pazo Fine Art / © Pazo Fine Art

Untitled, 1985 (detail)

Untitled, 1985 (detail), 97 x 32.5 x 24”

Untitled, 1985 (detail)

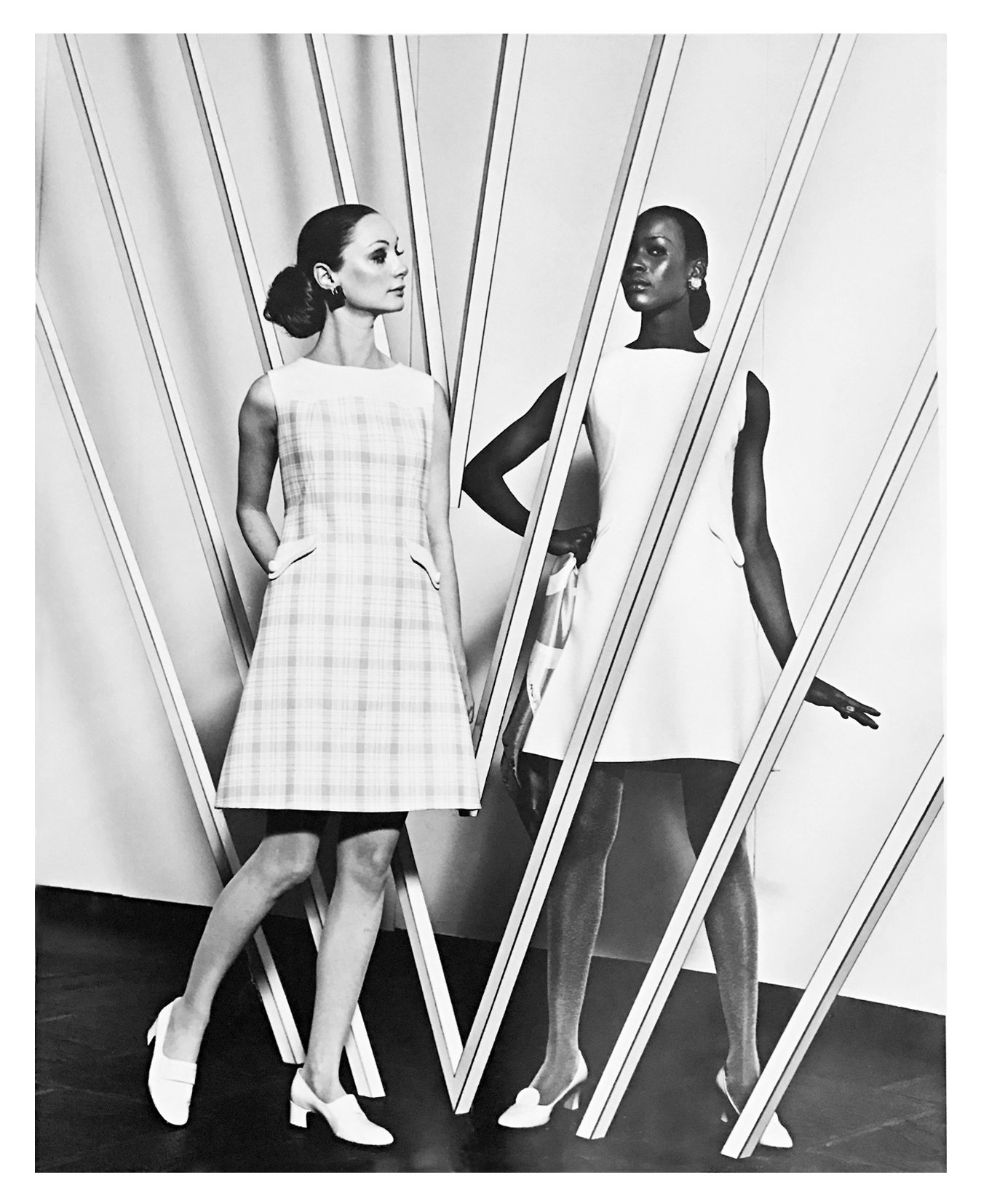

Photo © LeRoy Woodson. Photographed for the exhibition catalogue Rockne Krebs by James N. Wood, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York, 1971. Krebs in his studio working on a plexiglas sculpture, 1970.

Photo © LeRoy Woodson. Photographed for the exhibition catalogue Rockne Krebs by James N. Wood, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York, 1971. Krebs in his studio working on a plexiglas sculpture, 1970.

Ice Flower, 1969, 149 x 57 x 38" Collection: The National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC “Not long ago I visited a commercial gallery in the company of Michael Clark, a young Washington painter. A Krebs sculpture of transparent plexiglass stood tall and triangular in the center of the room. It was late afternoon. We turned the lights off to (text con't)

Untitled, 1971. Photo courtesy and © MMoCA, 2024. (text con't) discover which of the paintings on the wall would vanish in the semi-darkness and which would blossom. Clark suddenly turned and pointed at the Krebs. “Look,” he said, “a guardian angel.” Paul Richard, Washington Post art critic, 1968, essay for Plasticos 1968, exhibit catalogue, Latin American Art Foundation, San Juan, Puerto Rico.

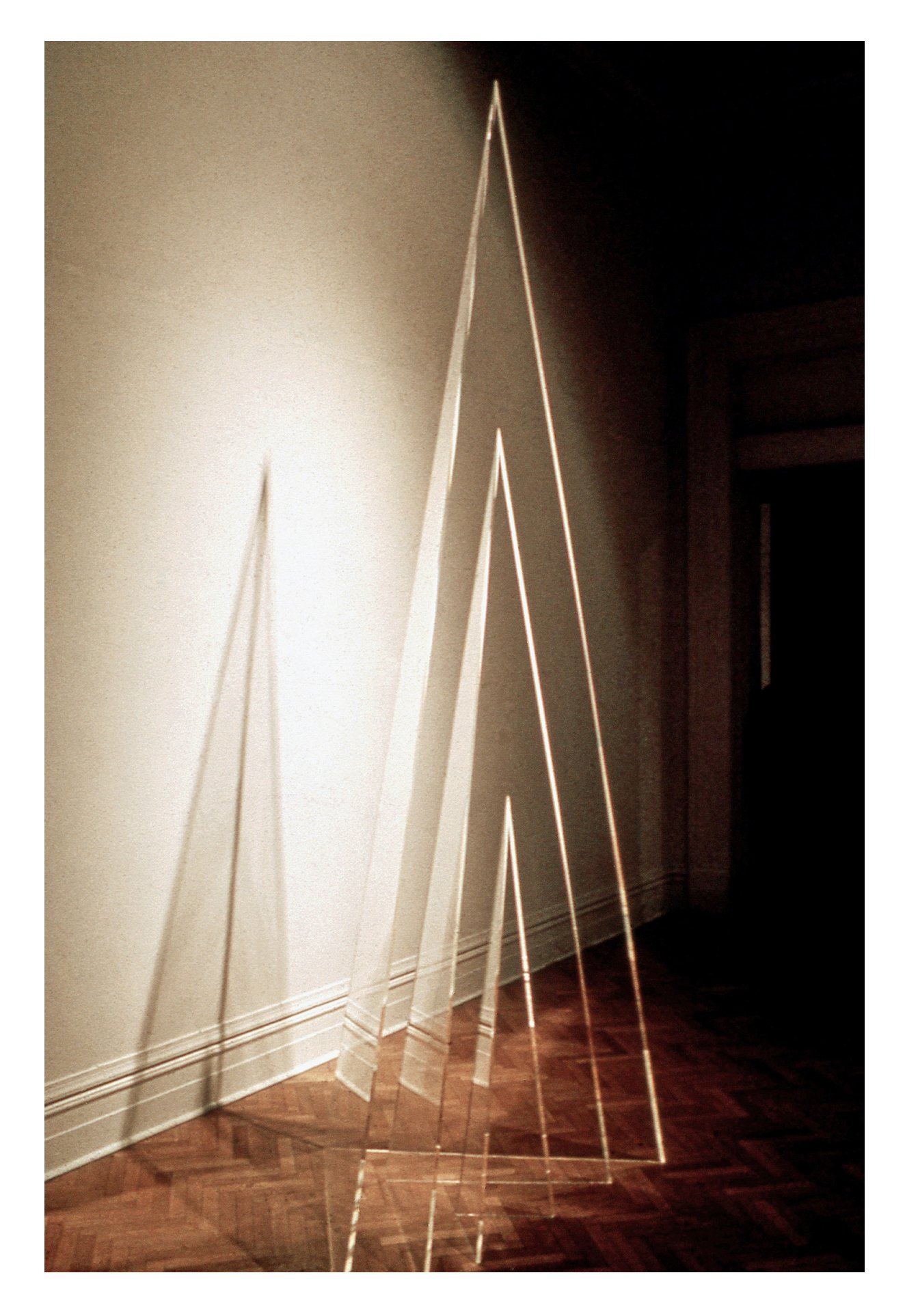

Untitled, 1968. Aluminum and light reflective tape, 154 x 154 x 120". Models in a fashion photo shoot, 1968.

Untitled, 1968. Aluminum and light reflective tape, 154 x 154 x 120". 1968: Rockne Krebs at the Whitney Museum of American Art in the Annual Exhibition Contemporary American Sculpture.

Untitled, 1968. Aluminum and light reflective tape, 154 x 154 x 120". “One is a room-activating composition of aluminum triangles... For the viewer feels as if Krebs has discovered something as monumentally simple as the triangle or the space within a room. It is this simplicity, rather than the shifting richness that swirl about it, that persists in the viewer’s memory." Paul Richard, The Washington Post, Restraint Enhances Young Washington Artist’s Sculptures, 1968.

Rockne Krebs exhibition The Study: Home on the Range Part IV, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, 1974. Paul Richard, an esteemed art critic for The Washington Post, is pictured with two sculptures by Rockne Krebs, titled "Between The Sheets," 1965, and "Untitled," 1966.

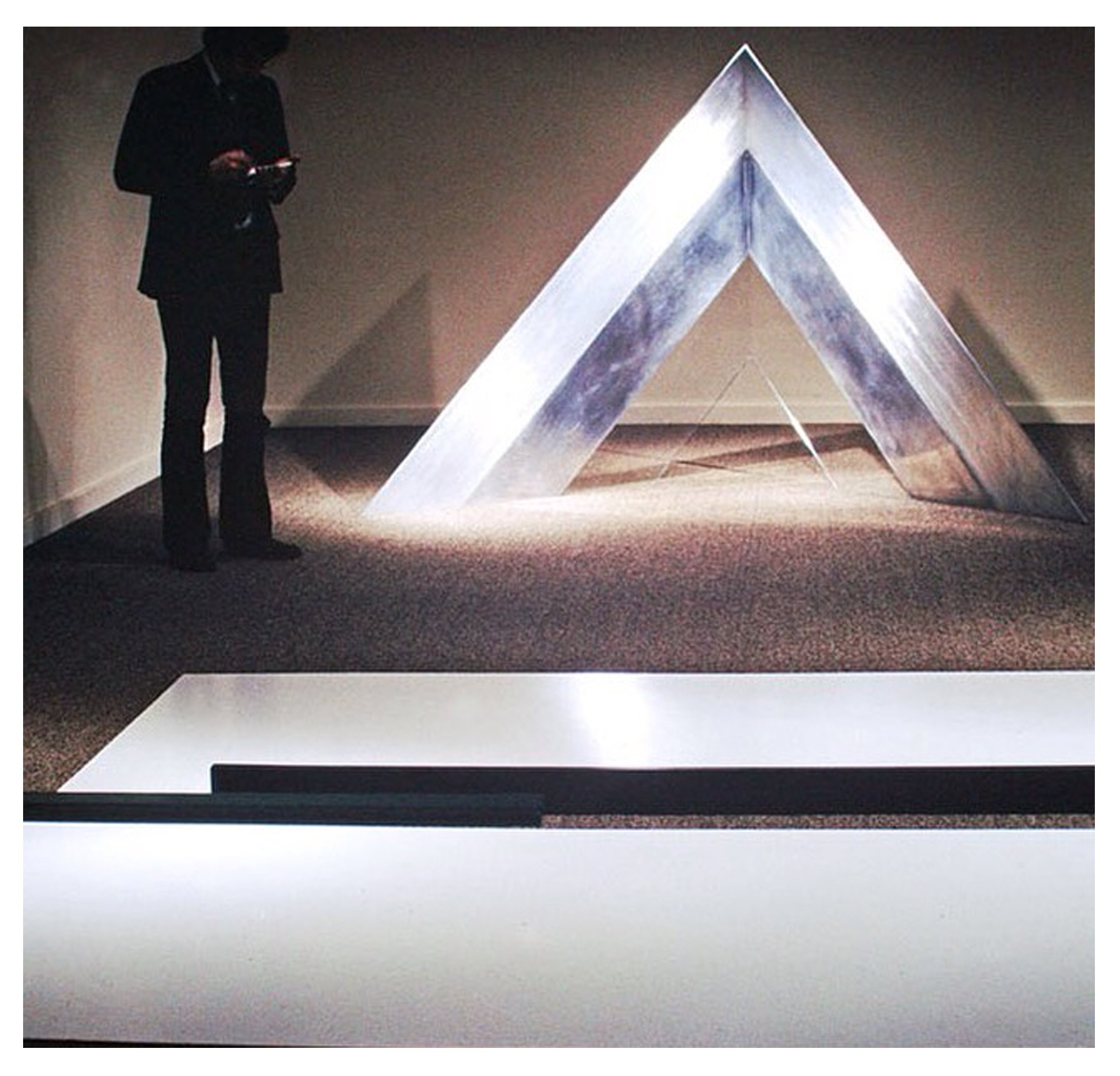

“There is a splendid symmetry in the exhibition of works by sculptor Rockne Krebs… It begins with the way the show is arranged in perfect balance: on one side of the Corcoran’s great atrium staircase is displayed in all its richness a retrospective selection of Krebs’ drawings from 1965 through 1982, and on the other side, the artist has placed one of his spatial structures, Crystal Oasis for the Winter Solstice.

On the one side, we are able to study as never before the complex development of Krebs’ sculptural ideas and work from the time he first arrived in Washington. And on the other we are able to experience directly just what the drawings are all about. From this ideal union comes a tremendously enhanced appreciation of the hard-won clarity and depth that Krebs has been able to bring to his art.

In a way Crystal Oasis does not need such support. Like Krebs’ previous environmental structure, this one stands on its own and is magically beautiful: three crystal palm trees shining in the middle of a darkened room. But the experience is unquestionably intensified by an understanding of how the artist reached a point of such seemingly effortless mastery.

The drawings stand on their own, too, and don’t necessarily need the completion of a structural environment. Krebs’ drawings are superb, though not in a conventional sense... Jay Belloli, who organized the drawing exhibition for the Baxter Art Gallery of the California Institute of Technology, correctly states that “the drawing are by far the finest record available of the size and range of Krebs’ accomplishment as an artist.”

Fundamental aspects of Krebs’ early sculptures were the clarity of their geometric forms (he was influenced by the Washington Color painters, particularly by Kenneth Noland’s chevron paintings) and the degree to which they attempted to encompass and even extend the whole environment instead of standing inert in the middle of a room…

But the rapidity with which he expanded his range of interests and his artistic vocabulary remains impressive to this day. Recognizing the vast space-framing spatial potential of a new instrument – the laser, invented in the late 1950s – he conceived his first laser environment in 1967. In 1969, on the occasion of the memorable three-artist Washington show organized by Walter Hopps (Krebs, Gilliam and McGowin), he began to use sunlight as a means to structure space.

At about the same time he began to experiment with prisms as a means to the same end. In 1970 he created his first outdoor laser piece. In 1971 he first conceived the idea of using a camera obscura, on a grand scale, to expand sculptural space by projecting the outside world into the darkened rooms where his environments were installed. These exhilarating experiments and discoveries are recorded in the drawings of the time, as well as his experiments with other immaterial means of forming spaces or adding to them… All the while Krebs’ stylistic vocabulary retained a strong, linear, classical sort of severity. If there was intellectual fire at the heart of the activity, it was expressed with icy purity.

His art is quite different now, a much larger whole, and it is especially interesting to witness in the drawings the ways in which he bumped and stumbled in a tireless expenditure of creative energy to find ways to make his sculpture say more, to incorporate autobiographical data and philosophical musings into the environmental works without spoiling their structural integrity…

The personal elements were expressed mainly in drawings and in three-dimensional pieces he titled (from his boyhood in Missouri) the “Home on the Range” series. Fantasy was one way – on paper he imagined vast, impossible structures such as a “Sun Pyramid,” and potentially fatal ones such as “Lightning Sculpture,” and brilliant, barely possible inventions such as “A Rainbow Tree.”

Humor and reverie were other means of expression: the drawings are full of puns, erotic imaginings and invented conversations with animate objects, such as the hilarious, if thoughtful, drawing whose script begins, “It began when a green pencil said to me…”

Gradually he began to bring the two sides together by learning how to deploy the full battery of his skills and tools in the larger laser environments. Among the devices he used were projecting real images upon walls by way of prisms mounted upon skylights (the huge eye in his piece for the Omni Center in Atlanta), and constructing laser housings that also functioned as independent, indoor sculptures (the “Home on the Range” construction for a cityscape laser in St. Petersburg, Fla.).

Above all this completion of Krebs’ art seems to have come from his dawning perception of the world as a unified whole to which every piece contributes – science, technology, his own artistic ego, man-made objects and the panoply of the natural world… His later works, frequently including images such as horses or trees, simply acknowledge more explicitly the ecological, spatial and symbolic possibilities.

Thus the Crystal Oasis for the Winter Solstice is indeed a fitting conclusion to the drawing exhibition, a brilliant coming together of techniques, images, structures, symbols and styles Krebs has been working out for 18 years. It expresses an aching desire to understand and to demonstrate the world’s transitory magnificence.”

Benjamin Forgey, Krebs: Crystal Clear,/ At the Corcoran: Brilliant Light, Brilliant Ideas, The Washington Post, December 24, 1983